Privacy 101: Privacy is more the responsibility of the listener than the talker - especially in the information age

This is my introduction to privacy, why it matters and why it's hard to grasp. When it comes to privacy in the modern age, your intuition is wrong. This leads to some huge problems that will only be fixed by changing the way we think and talk about privacy.

TL;DR: This TED talk is a great introduction to the issue.

Introduction

A friend posted another TED talk about how liking the "Curly fries" Facebook page is an indicator of intelligence (by correlation), as an introduction to the counter-intuitive ways in which our online data is used.

Big Data - the modern world of massive amounts of data and computing power - means *everything* you do online can be analyzed in this way, not just likes and public posts. Increasingly, what you do offline is also recorded and analyzed.

This video from New Scientist is a better one to watch as an introduction to the topic.

There's no way to live and contribute to society without giving away data - you can't really opt-out without opting out of society. Having very few likes, or no Facebook profile, is information in itself and may disadvantage you. When you go to a job interview, disclosing a lot of personal information is necessary, and now HR looks at your online profile before ever meeting you. Even if you don't use the Internet at all, you still have an online presence. This is not a bad thing in itself, it's just that there's so much data and computation now that it's very hard to know what people can learn about you from the other side of the world.

The Internet has given us more privacy in many ways. We can read, share and collaborate without the awareness of the people around us. It has increased freedom of speech in those countries that value it. But while we can keep our online activities private from our friends and family, it's becomingly increasingly impossible to keep them private from governments and corporations who deal in Big Data.

Over the last decade, our understanding of privacy has changed. Unfortunately this understanding hasn't filtered down from academia to the general public, because it's an answer we don't like.

Computational privacy

When I watched this presentation from privacy researcher Vitaly Shmatikov several years ago, it blew my mind because it turns on its head the way we think about privacy. Modern data-mining techniques are incredibly powerful. It's a bit technical but the implications are massive: for the future of the Internet and society itself. If you're not mathematically-minded, skip to 22:40. If you prefer, you can read the transcript.

To summarize:

- Seemingly anonymous data about people actually leaks information about the people in it.

- Even purely statistical data can leak personal information if the changes can be tracked over time.

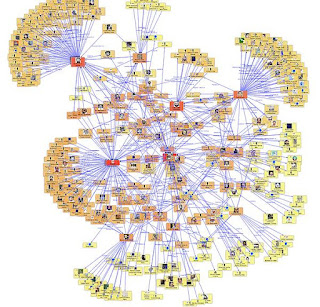

One example is how the anonymous graph of a social network (all labels removed, just a set of connections between identical nodes) can be de-anonymized by comparing it with another social network that isn't anonymous.

For instance, let's say you have a Twitter account that you are very careful to keep anonymous - perhaps you're a political dissident in an authoritarian regime, perhaps you want to talk about being gay in a country where homosexuals are stoned, or perhaps you're a civil servant and need to separate your personal views from your official position at work. You also have a public Facebook profile (or LinkedIn, or whatever). Let's say your Twitter account has 50 followers, and you have a similar amount of Facebook friends (or LinkedIn connections). It turns out that if someone has access to just the map of both networks (both totally "anonymized"), if you have only 3 or 4 friends in common between the two networks, that is probably enough to link the two identities with a high degree of certainty. Then the match can be confirmed using other data such as writing style, timing of posts, etc.

Crucially, this applies to any social network, not just online ones. It could be an anonymized graph of sexual relationships, or location data (e.g. two people are linked if they keep showing up in the same area at the same time).

There are three key concepts to remember:

- Anonymization of data sets doesn't work.

- There is no such thing as "Personally Identifiable Information" because all information is potentially identifiable.

- Privacy is a function of computation, not a function of data.

This is a revolution in the way statisticians and computer scientists think about privacy. Where previously they thought in terms of anonymization, they now consider differential privacy. Differential privacy guarantees that your risk of being identified isn't increased by being included in the data set.

As a consequence, there are some common promises that cannot be kept by those making them:

- "We do not collect/disclose personally identifiable information" is always false.

- "This data is anonymous" or "this is an anonymous survey" is always false, unless:

- People analyzing private data sets need to:

- Maintain proper and accountable access control

- Use a system guaranteeing differential privacy

For instance using a system like Airavat which integrates mandatory access control with differential privacy. Unfortunately, no-one does this, because it's difficult and limits what kinds of analysis can be done, and there's no demand for it. Yet.

Doctors are beginning to be concerned about how their patients' data is being used. Healthcare is likely to be the first area where differential privacy is taken seriously, due to its sensitivity and the fact that private companies have made a business model out of bypassing medical record privacy.

Why does it matter?

Privacy isn't about keeping secrets or hiding wrongdoing. Privacy is a human right because it's essential to human dignity. It's about protecting against misunderstandings and abuse of power. See this essay by security expert Bruce Schneier, or this from privacy researcher Daniel Solove.

I posted this a few weeks ago: The story of a sociologist who tried to keep her pregnancy hidden from online advertisers. It was very difficult, but she learned how, and as a result was suspected of being a criminal.

I wrote previously about how advertising networks track your online activity - even when you take steps to protect yourself, such as blocking cookies or hiding your IP address as this woman did. Governments also invade your online privacy in the name of security. But doing so reduces security for everyone.

Of course it goes far beyond what you do online. So much of what you do can be tracked, identified and analyzed, whether location data (eg your phone, photos you post online, your face or license plate on surveillance cameras, digital transactions), biometrics you leave behind (fingerprints, DNA), behavioural biometrics like your voice, patterns of speech, handwriting, typing patterns, writing style, gait... For more on that topic, see the blog of top privacy researcher Arvind Narayanan.

Consider the "right to remain silent", the Miranda warning "anything you say or do can and will be used against you in a court of law": Lack of privacy may get you arrested and jailed, even if you're innocent.

History shows privacy invasions aren't just a problem for people trying to hide wrongdoing, they're also a problem for people who disagree with something a powerful group is doing - people who are trying to change society for the better, like those who led the movements to end slavery and apartheid.

What does it mean, that privacy is a function of computation, not data?

The commonly held belief is the responsibility of privacy lies with the person doing the talking: if you want to keep something private, don't share it. We forget the responsibility of the listener (or the watcher). Once you learn something, you are responsible for what you do with that knowledge. Big Data makes this latter responsibility much clearer - those doing the analysis are responsible, not the people being analyzed who have no control over it, and who are probably not even aware it's happening.

This is not something we want to hear - we want to be free to do what we like with the information we receive. We want to have great power but no responsibility.

Big Data is used to justify racism, sexism, ageism - it's about applying labels to people, and if certain labels fit you will be discriminated against. This is common in advertising, and of course price discrimination is pervasive and as old as money itself, but more importantly, governments do it to identify potential criminals and terrorists. Factors that increase your suspiciousness in the US include being Muslim, playing paintball, practicing martial arts, being interested in military tactics, electronics, chemistry, or especially privacy (like the pregnant sociologist above). And of course criticizing the government.

How did it get this way?

Thanks to Chelsea Manning and Ed Snowden, government abuse of privacy has gotten attention. See my latest post on the hypocrisy and double-speak of surveillance agencies like the NSA and the GCSB.

The corporate side, like the curly fries thing, gets less attention. Corporations won't fix the problem, because privacy is a lemon market - consumers *can't* make good decisions about their privacy.

It's part of a bigger issue: All over the world, we are abdicating moral responsibility to the marketplace. But the marketplace is amoral. As a society we need to talk a lot more about what is okay and what isn't, what we want to be sold to the highest bidder and what should never be sold.

(This post was originally posted to Facebook; see further updates and comments there)

Comments

Post a Comment